Answer 1

A single nodule, between 1 and 6 cm in size without identifiable lymphadenopathy or effusions in a patient without symptoms or physical findings suggestive of a specific diagnosis such as pneumonia or cancer.

Answer 2

Primary lung cancer, metastatic cancer, scar/granuloma, infection, inflammatory lesions such as sarcoid/Wegener’s, congenital lesions such as cysts, pneumoconiosis.

Answer 3

Try to obtain any old chest x-rays. The vast majority of lesions which have remained radiographically stable for 2 years are benign and require no further evaluation.

Answer 4

CT scanning is useful in evaluating a solitary pulmonary nodule both for (1) identifying unsuspected lymphadenopathy, effusions, and/or other nodules which were not identified on routine chest x-rays, as well as (2) further characterizing the nodule and, in so doing, raising or lowering the chance of the lesion representing cancer:

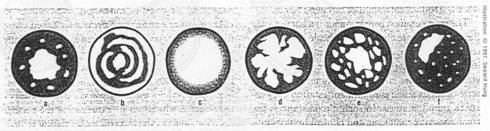

Pattern of Calcification:

Most Likely Benign – central, laminated, diffuse, popcorn (a-d)

Benign or Malignant – speckled (e), eccentric (f), and non-calcified

Size:

In general, most benign nodules are small (< 2 cm) and larger lesions carry an increased chance of being malignant.

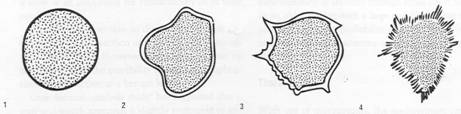

Border:

Benign – smooth and regular, or lobulated (1 & 2)

Malignant – irregular, or spiculated (3 & 4)

Answer 5

Stage I (T1N0M0). Expected five year survival of 60 - 80%.

Answer 6

Virtually all patients with known and/or suspected lung cancer under FDG-PET scanning. The reported sens/spec for 1 cm or larger pulmonary nodules averages 95%/75% in the literature. Hence, PET scanning is highly sensitive (95%) and moderately specific (75%). Please emphasize that PET is helpful in different ways in different patients:

Answer 7

In general there are three major options:

Surgical Resection:

Surgical Resection offers a number of advantages in this scenario. In simplest terms, this lesion is either malignant or benign.

If it is malignant, surgery could be potentially curative. Clinically this patient would be staged as a Stage I, T1N0M0, lesion and if surgical staging remained the same, the patient would have a great chance of being cured by surgery (as above).

Unfortunately, even if it is benign, biopsy rarely excludes the diagnosis of cancer and as such one would recommend surgery anyway given the chance of curing the patient given its early clinical stage if it is malignant.

The obvious down side to immediate surgery is that if the lesion is benign, the surgery will appear to have been unnecessary in retrospect. This must be discussed with the patient and his/her personal comfort level with the various strategies should ultimately guide this decision.

Biopsy:

(CT guided fine needle aspiration or bronchoscopy)

Biopsy is rarely indicated given the discussion above. Biopsy may be useful if the chance of a benign lesion is high and biopsy can be done with little or no risk. Biopsy may also be useful when the patient is at high risk for surgical complications and/or is not a candidate for surgical resection. In this latter situation, biopsy would be necessary in order to establish the diagnosis so that non-surgical treatment might be initiated – i.e., radiation therapy.

Observation:

Careful, ACTIVE, observation (typically with repeat imaging every 3 months for two years) is sometimes the preferred recommendation. This is especially true when the patient is a poor surgical candidate or when the chance of malignancy is low. If the lesion remains stable for two years, it can safely be assumed to be benign. If however the lesion grows during follow-up, the patient should then be taken for surgical resection.

Overall , given this patient’s risks of cancer (age and smoking history) and lack of significant surgical risks, the patient should be evaluated for surgical resection (assuming that CT scan revealed no lymphadenopathy or other lesions).

Answer 8

Pulmonary Function Testing should be performed in all patients prior to lung resection. A pre-op FEV1 of greater than 2 liters and/or a predicted post-operative FEV1 of 0.8 liters is required prior to lung resection.

Answer 9

A single lobe resection would be predicted to remove 20% of lung tissue and hence result in a predicted post-operative FEV1 of 80% of 1.5 liters = 1.2 liters and as such the patient would be considered to be an acceptable risk for resection.

Answer 10

If the predicted post-operative FEV1 is too low (i.e., less than 0.8 liters) one might perform quantitative perfusion scanning to identify truly how much perfusion is directed to the area which is to be resected. Often times, the area to be resected (because it has been partially replaced by tumor) has less than the predicted amount of perfusion and thus is relatively non-functional and can be safely resected.

Answer 11

This remains a controversial subject. At the present time, no national organization (i.e., ACP, ACCP, AMA, etc) advocates for screening for lung cancer. These recommendations are based upon several studies, the most widely quoted of which is the Mayo Lung Project (MLP). In the MLP, patients were randomized to either (a) CXR plus sputum cytology every four months vs (b) standard of care. No difference in overall mortality was observed. However, the standard of care group actually received yearly CXR’s as well; hence there was no true control group. More recently, the ELCAP (Early Lung Cancer Action Program) reported its data from using CT scans to screen for lung cancer. These non-randomized data from 1000 patients showed a 2.6% incidence in stage I lung cancers. These cancers were resected and, theoretically, these patients could be viewed as having been cured of an occult malignancy. However, until randomized prospective data demonstrate an improved mortality with screening, routine use of CT’s is not recommended. Nonetheless, many patients and physicians alike are including this modality in high risk patients.

Importantly, even as of 2009, there are no randomized trials showing a benefit with using CT to screen for lung cancer.